The Optimist Creed |

Once organized, Optimists began looking for a motto, a slogan or a creed they could live by. Many were suggested; none were quite what was wanted and needed. In Los Angeles, soon after the end of World War I, the wife of James V. Westervelt, the club bulletin editor of the Optimist Club of Los Angeles, found a small item on optimism in a local newspaper and gave it to him thinking he might be able to use it. Westervelt reprinted it in the club’s 1919 yearbook under the title “Promise Yourself.” As the original newspaper article did not identify the author, Westervelt labeled it simply as “Selected.” It contained ten resolutions or promises a person could make to himself and that, if they were kept, would give them guidance throughout their life. Members of the club copied it, and a couple of years later when they journeyed north to recruit new Optimists and build new clubs in San Francisco and Oakland they took it with them. In this short document, they felt, could be found all that Optimism is and Optimists should be. |

James V. Westervelt |

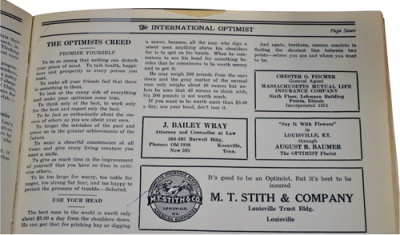

The Optimist, December 1921 |

With so many California Optimists familiar with the piece, it was inevitable that someone would send it to The Optimist magazine, where it appeared in the December 1921 issue. When the next convention was called to order in Kansas City in 1922, nearly every delegate present had a copy of “Promise Yourself” in his pocket. Hundreds of copies had been brought and distributed by Optimists from San Francisco and Oakland. Still without knowing the author, the convention adopted it as The Optimist Creed. Beginning with the August 1922 convention issue, the Creed became a regular feature of The Optimist magazine. |

Jim Westervelt, however, was curious about who the author was. After a little literary detective work he found that “Promise Yourself” first appeared in 1912 in a book titled Your Forces and How to Use Them by Christian D. Larson. Its theme was simply “you can do anything you want to do if you only set your heart and mind to it.” It was a small volume of high inspiration and philosophy, one of many like it that began appearing on the market shortly after the turn of the century. All were outgrowths of the “Transcendentalists” of the day, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Thoreau and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Larson, who wrote 39 other books in his lifetime and gave more than 5,000 lectures, began his career in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1898 lecturing in public halls, private homes and surrounding towns. His teachings led to the founding of the New Thought Temple of Cincinnati, which became one of the largest and most successful and influential institutions of its type. Larson was also the founder of—and for 25 years the editor of and chief contributor to—a monthly publication called first Eternal Progress and later New Progress. At one time, its circulation reached 150,000 with subscribers in every English-speaking country in the world. At every international convention from 1922 until Larson’s death in 1962, delegates telegraphed greetings and reaffirmed their appreciation of their creed to its author. The Organization Becomes Truly International As the months rolled by through 1921 and 1922, Optimism spread in all directions until by 1923 there were 59 clubs with 4,500 members. And though the years ahead looked even more promising, there was one door that had not yet been opened, one avenue of progress that had not yet been entered. |

From its birth at the Louisville convention the organization had been international in name only. But no one knew how and when it would become truly international. And then, out of the blue, during the latter part of 1923 the answer came in the form of a telegram to the Optimist office from a young man in Toronto, Ontario. William M. Skilling, known as “Bill,” was a wounded Canadian Army veteran of World War I who returned to his country in 1920 with a war disability and in such wretched health that he had difficulty finding a job. Having hit bottom in the morale department, Skilling happened to hear of a club of men called “Optimists” while visiting in the United States. His telegram to the Optimist office sought to receive permission to start a club in Toronto. On December 21, 1923, Bill Skilling and two friends, Dr. Ben Stephenson and C.S. Dawes, began organizing the first Canadian Optimist Club. On the night of February 26, 1924, at a banquet in the ballroom of the Prince George Hotel, the “club that made Optimist International international” received its charter from the president of Optimist International, James W. Chilton. Also present were the president and secretary of the nearest club, the Optimist Club of Buffalo, New York. Four months later, on June 4, 1924, the second Canadian Optimist Club was chartered, in Hamilton, Ontario, about 40 miles west of Toronto. It had been built by Bill Skilling, who had been named the first Canadian field secretary. |

|

Just four months after becoming truly international, Optimist International welcomes its second Canadian Club -- the Optimist Club of Hamilton, Ontario. |