| Early Optimist Youth Work Early records indicate the first Optimist Clubs soon became interested in helping the boys of their communities. They show that it was not long after men began assembling as Optimists before the altruism of this basic philosophy led them away from their interest in helping each other through business reciprocity and into the desire to help someone else. |

|

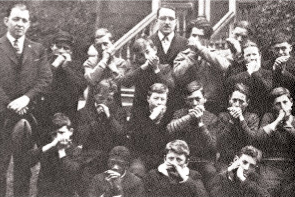

By the time of the first convention in Louisville in 1919, nearly every Club was reporting some activity in the field of what was then called “boys work.” There was talk then of encouraging all Clubs to do likewise, but no concrete program or procedure or even a slogan was suggested to the delegates. Even so, many Optimists and individual Clubs were already involved in the then-popular Big Brother movement, as association designed to work with juvenile delinquents. Because of this work by many Optimists, it was quite natural that some began to think of themselves as “Friend of the Delinquent Boy.” |  One of the first youth activities sponsored by the Optimist Club of Toronto was this harmonica band of the Jarvis Street Auxiliary School. The principal of the school was William J. Tamblyn, center rear, who became President of Optimist Internationational. One of the first youth activities sponsored by the Optimist Club of Toronto was this harmonica band of the Jarvis Street Auxiliary School. The principal of the school was William J. Tamblyn, center rear, who became President of Optimist Internationational. |

|

It was the doctor’s theory that thegreatest service an Optimist could perform for a boy was to convince him that Optimists are sincere in their efforts to help boys help themselves. Response to the challenge from Dr. Hartloff was enthusiastic. In the months that followed, word came from throughout the organization that Clubs were doing more than merely talking about the problem over their luncheon coffee. By the time of the fifth convention in Chattanooga in 1923, when the organization’s name was changed to Optimist International, the business of boys work was an item of prime importance on the slate of many Optimist Clubs in the land. Jay C. Goodrich, then International Field Secretary, told the convention: “We shall strive to make the Optimist Club known to the world as the ‘Friend of the Delinquent Boy.’” Delegates then officially adopted the organization’s first slogan. It appeared on the front cover of the July 1923 Optimist magazine for the first time. Later that year, the Optimist Club of Cleveland, Ohio, requested that the International Board of Directors give “most serious attention to the question of selecting certain objectives which the local clubs may advance. That the affording of increased educational opportunities to the boys of any community … would be a work upon which the Optimist Clubs might well concentrate their efforts.” In preparing for the 1924 convention that they would host, Optimists from the Milwaukee Club wrote to the International Office to ask if there had been created a definite program that local clubs could follow in carrying out the work with young delinquents. The still young and inexperienced Optimist International officials of 1924 could only reply that the organization had no definite plan to recommend and that the only advice they could give was to “tackle the problem along general lines.” They suggested that local Optimist Clubs cooperate with the Big Brother movement and other such organizations already set up for the purpose. But the Milwaukee Optimists weren’t satisfied. When the convention convened that summer they presented a plan in the form of a resolution. First of all, they felt the word “delinquent” in the Optimist slogan was poor psychology. And while much of the work being done was among boys with records in juvenile court there were still many hundreds of other boys brought into the program who by any stretch of the imagination could not be classified as delinquents. Their resolution also asked that Optimist Clubs secure a pledge from their members to devote several hours a week to one or more boys during the year following the signing of the pledge. |

| Following the convention, during which the organization’s official slogan was changed to “Friend of the Boy,” the executive committee of Optimist International began to develop a plan for financing the salary of an expert in boys work “who shall have charge of further developing and carrying on boys work by Optimist International.” The thinking was that if this “Friend of the Boy” business was to get off the ground someone was going to have to direct it. |

|

Questionnaires were prepared and mailed to all Clubs, asking what kinds of boys work they were trying to do, how successful they had been and if they had any ideas for the international planning. Some were returned with sketchy information. Others answered by saying they were pretty confused about the whole thing. Still others registered surprise. They didn’t even know they were supposed to be doing boys work. Many Clubs didn’t respond at all. By 1927, Optimists were hard at work in many programs for their friend, the boy. In general, the problems of youth in one city were about like those in any other. But each community had its own solution, its own best way to find the answer. Consequently, a Boys Work Council was established that year to incorporate the best features of various boys work proposals and establish some broad lines of policy by which Optimist Clubs could cooperate with various civic institutions. The Council came to the 1928 convention with a program to recommend: Optimist Clubs should continue their efforts in the Optimist Uncle plan (by which an individual Optimist becomes advisor, helper and friend of a boy referred to him by the juvenile courts) and in the Junior Optimist Club program which had blossomed just a few years earlier. Optimist boys work programs were booming and the leaders of the organization felt it was time to provide them with the finances needed to grow. The delegates at that 1928 convention instructed the Board of Directors to set aside 25 cents of every Optimist’s dues and use that fund for boys work on the International level exclusively. The First Youth Clubs A few days after school started in Milwaukee in 1920, Henry Scarborough, a member of the Optimist Club of that city, received a phone call from the local YMCA secretary. “Henry,” he said, “we’ve got a project going here and we need your help.” The project was a “Find Yourself” campaign for the boys of Milwaukee, both “Y” boys and non-members. The object was to help the boys discover their aptitudes and make the right choice of vocation for which they could prepare. For several weekends Scarborough served as interviewer and counselor in the “Find Yourself” campaign. And from those sessions came a permanent organization of boys who had found an understanding friend and a wise counselor. They wanted to remain together as a group and they wanted his Optimist Club to stay with them. Scarborough agreed to serve their boy-type club as sponsor. When a proper name for the club came up for discussion, the boys had a logical choice. “Mr. Scarborough, you’re a member of an Optimist Club for men. Would it be OK if we called ours the Junior Optimist Club?” The original Junior Optimist Club adopted a constitution, worked out its bylaws and objectives and began to meet regularly. When summer came again the young members were brought even closer together by picnics, parties and camping trips. Like their elders before them, however, they weren’t long in coming to realize that the richest rewards from such an organization come from helping others as well as themselves. They went to work for poor families, they lent the “Y” an energetic hand in its membership, finance and other campaigns. |

With the 1924 Convention approaching, Optimists were encouraged to "keep your eyes on Milwaukee." |

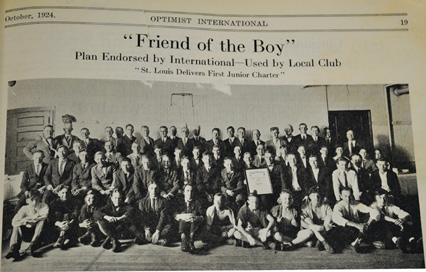

And four years later, in 1924, when Optimist International convened in Milwaukee, that first Junior Optimist Club was the hit of the convention. Inspired by the enthusiasm of those youngsters, the delegates voted the right of Optimist International to charter Junior Optimist Clubs everywhere. The only provision was that each Junior Club must be under the supervision of a senior Club and under the direct leadership of a member of that senior Club. |

The idea spread like wildfire across Optimism. It did not exactly stagnate in the city of Milwaukee either, for Junior Optimism grew from that first Club of a handful of boys to a peak of 42 Clubs and several hundred members in the years immediately prior to World War II. Milwaukee, however, was not the only city in which Junior Optimism had begun to flourish even before the 1924 convention there and the decision to grant charters from Optimist International. In 1922, in St. Louis, an Optimist named Tom Elliott who, incidentally, would later become the first Executive Director of the organization, pioneered a similar trail. He was familiar with the tough neighborhoods of St. Louis and the boys who lived there, many of them facing a future of homelessness and crime. He decided to try and get a few of them together and organize a small club of some kind. Only five boys showed up at the appointed time and place for the first meeting, but before long the group had grown into a club of 30 to 40 members. When Elliott proposed they come up with a name he found that the matter had already been settled. They told him they were already calling it an Optimist Club. Elliott was flattered but explained that it might be confusing and suggested they tack on the word “Junior” on the front of their Club name. Within six weeks after the Milwaukee convention, the St. Louis Junior Optimist Club had met the requirements and applied for its charter. It was the first to be received and the charter was granted on August 5, 1924. It was Charter No. 1. Two other Clubs applied for charters before the year was out and then, on January 10, 1925, came the application from the oldest Junior Optimist Club, the one Henry Scarborough had started in Milwaukee five years earlier. For a few months it operated under Charter No. 4, but at a meeting of the International Executive Committee this was changed. In recognition of its claim as the original Junior Optimist Club its charter was re-issued as No. 1-A. |