The 1930s: Optimism and the Great Depression

| By the time of its 10th anniversary, Optimist International was beginning to experience the growing pains of an organization expanding over the land faster than its succeeding administrations could keep up with it. From a few enthusiastic Clubs functioning in a few far-flung cities, the organization had grown to 117 Clubs in its first decade, with more than 8,000 members in the United States and Canada. And while Optimism was high at that summer of 1929 meeting, dark clouds were looming in the world that would put heavy pressure on the fledgling organization’s efforts to survive. On October 29, 1929, the U.S. stock market crashed. The Great Depression was on. Hardly on its feet, Optimism now faced its greatest challenge. Never were its philosophies so sorely needed; never before had the opportunity to serve been so great. With each passing month the need for someone, some organization, to indeed be a “Friend of the Boy” became more and more acute. Many Optimists themselves were caught up in the swirling tide and, unable to maintain their own incomes, were forced to withdraw from their Optimist Clubs. Membership rosters across the land began to dwindle. The International program suffered in turn as revenues from dues diminished. More money was needed in the International treasury to meet its obligations and to take up the slack caused by certain Clubs that were having a tough time, too, and were falling behind their dues. Things didn’t improve over the next few years. In fact, at a meeting of the Executive Committee of Optimist International, 1933-34 International President V. Ernest Field reported an emergency within the organization, a crisis comparable to that of the United States government itself. “Losses in numbers and in morale, due to the time,” he said, “are so heavy that if continued can mean the end of Optimist International.” To counteract this, he proposed a plan of progress built on fellowship, reciprocity, membership, boys work and new Clubs. “Our objective,” Field declared, “must be a net gain of 1,500 members in Clubs and 150 new Clubs!” |

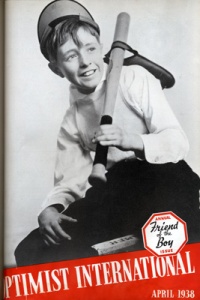

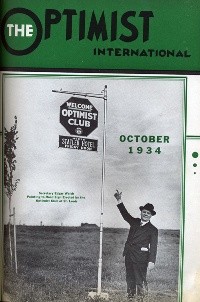

During the years of the Great Depression, Optimist International's role as "Friend of the Boy" was needed more than ever before.  In the early 1930s, Clubs were encouraged to cooperate in a publicity program by placing signs along roads that led to their cities. |

Therefore, at the 1935 convention in St. Louis, Optimists agreed as a matter of policy that business reciprocity among members was normally the natural result from close contact and friendship among those who worked together for others, and that too much emphasis on it for purposes of gaining members or in new Club building could be harmful. Concern was also noted that an ambitious boys work program might throw too great a responsibility on already financially embarrassed Club members and that elaborate and expensive programs for boys were creating a burden beyond what could be called reasonable during a financial crisis. And while 16 new Clubs had been established during the 1933-34 year—built by professional organizers – the funds of Optimist International were running low. Several members, most of whom had been active from the start of the organization, signed a note together for sufficient funds to operate for the balance of the year. Shortly before the 18th annual convention in Fort Worth in 1936, Immediate Past International President Henry Schaffert approached International President Walter J. Pray with a plan to help raise funds to keep the organization going. He admitted that the plan wasn’t original with him because he had seen it work with other organizations and several country clubs. Pray agreed with the proposal and allowed Schaffert to address the delegates. |