The 1940s

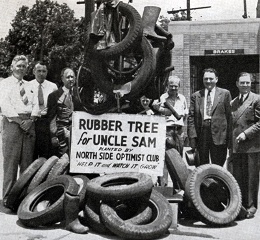

Clubs collect towers of rubber tires during the war. |

Junior Optimist boys help with the cause. |

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany marched into Poland. Two days later Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. A week later, on September 10, Canada entered into the war. The surprise attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, forced the United States into the global war. In both Canada and the United States all efforts turned to the all-out war pursuit. Civilians turned full attention and devoted every effort to production of materials for war. There was some sentiment at the time that all service clubs should be disbanded for the duration of the war. Of course, Optimist Clubs in both the U.S. and Canada had been quick to pledge their support to their governments and to promise manpower necessary for all community wartime projects. |

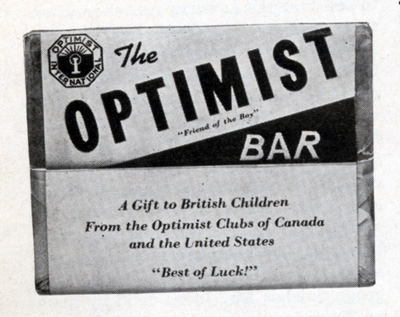

One of the most necessary of those projects was the collection of scrap metal to make up for the normal peacetime supplies that would soon be exhausted in the all-out manufacture of arms and munitions. The U.S. called upon its citizens to salvage 17 million tons of scrap metal. Optimists’ concerted effort in this and many subsequent home front campaigns during World War II is considered by many as the organization’s highest achievement. In Canada there was growing concern over the needs of children living overseas where the fighting was. Out of this concern arose a project that spread across the nation, appealing to hundreds of thousands of Canadians. Originating with the Optimist Club of Welland, Ontario, it was based on the conviction that children were entitled to a few little luxuries just because they are children and that the war had deprived them of these as well as many of life’s necessities. |

|

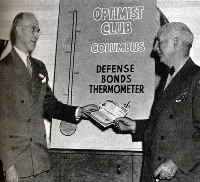

With the Optimists leading the way, the Chocolate Fund was established to pack and deliver to British children, through the British Food Ministry, the schools and the Red Cross, more than two million bars of chocolate. For thousands of youngsters this was the only sweet they knew during ten years of war. The value of Optimist International to the war effort was proved in many other ways time and again. Millions of dollars were raised in Optimist-sponsored bond drives. More than 1,600 Life Memberships were purchased with $100 war bonds. Servicemen’s centers at home were provided and staffed by Optimists. Untold thousands of servicemen overseas received letters and gifts from the Optimist Clubs in their hometowns. By the end of the war nearly 2,000 Optimists were in uniforms of the Canadian and United States militaries. Nearly 1 out of every 7 members served their country during this time. Along with every other organization, Optimist International found its efforts to grow severely restricted by the war. Its field staff resigned in 1942 to enter military service and new Club building came to an abrupt standstill. Fewer than a dozen new Clubs were chartered during the war years. Surprisingly, however, total membership actually increased during this period, from 13,000 in 1941 to 16,000 in 1945. The wartime service efforts of Optimist Clubs attracted many who could not serve their countries in the military but felt they were contributing by getting involved in an organized effort on the home front. During the years of World War II there were no international conventions because of travel restrictions and the need for every Optimist to remain on the job until the war was won. Conferences were held instead to carry on the administrative work of the organization. The training of incoming Club and District officers became, for the first time, the responsibility of the District Governors. |

More than 1,600 Optimists purchased Life Memberships with $100 bonds. |

|

At the 1942 Wartime Conference reports were received that despite the huge efforts of Clubs to contribute to the war effort boys work had not suffered. In fact, the average amount of time and money per Club devoted to youth service had increased throughout the organization. To meet this problem, Optimist International established a goal of 500 Life Memberships to provide for the postwar building of new Clubs. By 1944, nearly 600 had been sold and the organization was ensured a sound financial structure upon which to build when the war came to an end. |